- Home

- Jocks, Yvonne

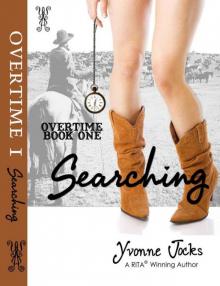

OverTime 1 - Searching (Time Travel) Page 2

OverTime 1 - Searching (Time Travel) Read online

Page 2

From him that seemed positively chatty, but apparently the mood for gab left him just as quickly. He applied his spurred heels lightly to his horse and headed out, me and the five others in tow.

The herd... and he wore a cowboy hat. Maybe I was on a ranch. Though somehow disconcerting, that thought also pleased me—that I independently knew about ranches, too.

"If you don't know who I am, how come I'm riding with you?" I asked. Wearing your clothes, I added silently. Using your saddle.

For a minute I thought he wouldn't answer at all. He didn't turn to face me. Then he said, "Found you."

"When?"

After a similar pause, he said, "Mornin'."

"Where?" He'd better not say Kansas—I had access to his rifle.

"Creek bed," he admitted, and his voice took on a hollow, confused tone. "No wagon. No tracks. No flood sign. Jest you."

He must have put clothes on me, hoisted me onto his horse, and ridden on. I wasn't sure what to feel about his having seen me naked. Modesty diminished in importance somehow, compared to lying unconscious in a creek bed with no memory.

Compared to fear, compared to abduction, compared—

I threw up some of the water, coughed on it, fought to catch my breath. Don't think of that! It's not real!

Not anymore, anyway. Not at this hot, blue-skied, horse-scented moment.

I caught him peeking over his shoulder at me—disgusted? Concerned?

"Thank you."

"Couldn't rightly leave you." He didn't sound particularly enthusiastic. The same statement would work about helping some injured animal he might find. Couldn't rightly leave it.

Maybe enthusiasm is overrated. Whoever I was, whyever I was here—I was with someone who'd given me water, and a bandage, and a potty break, and who kept me from getting sunstroke. Someone who could handle seven horses when I couldn't handle one. Someone competent.

Unlike me.

I could, at the moment, live without enthusiasm.

Chapter 2 –Garrison

Is silence natural? It didn't feel natural to me.

We rode through a harshly beautiful countryside, open and wild—and ungodly monotonous. Flat, unmowed grass stretched around us, and pale sky domed above us. A hawk or an eagle or something—something big with wings, a vulture?—circled for awhile. Despite nature's bounty, or maybe because of it, the need to speak built in my chest. It didn't seem natural to go this long in another person's company without words, or music, or… something. I tried to distract myself, to discover further clues to my identity, but had too much—and too little—to think about.

Too damn quiet around here!

"So," I said finally, "these are your horses, huh?"

My companion didn't even turn to look at me. On we rode.

"So," I tried again after a minute—maybe he hadn't heard—and he said, "Ain't no horse thief."

Touchy! "I didn't mean to imply you were! It's just... I don't think I've ever had a horse." I considered my discomfort about being this high up, my ignorance about which side to board and unboard on. "Or if I have, we weren't close," I conceded with a shaky grin.

We rode on in silence, between unending grass and unending sky. My grin got tired and went away, unseen. And on we rode.

"So you're pretty good with horses, huh?" I tried, after awhile. I didn't get a reaction—he just double-checked the rope leads. Then again, my compliments in the area of horsemanship wouldn't carry much weight. He probably figured I'd say the same thing to anyone who could climb on unassisted.

"You must like them," I prodded. "Huh?"

"They're horses," he said, as if that were self-explanatory. It wasn't. Did he mean, of course I love them, they're that most wondrous of beasts, horses? Or maybe, Why would I? They're merely horses, after all?

"Do you own a lot of them?" I asked, and he finally glanced in my direction. His heavy brow was furrowed, giving him an oddly endearing, lost look for a cowboy—had I confused him?

"More than ten?" I clarified.

He nodded, and looked ahead.

"More than fifty?" I pursued.

Nod.

"More than a hundred?"

"Near 'bout."

Ask open-ended questions, I prompted myself. "What do you use them for?"

He glanced toward me again, neither confused nor endearing, and I raised a hand to fend off what looked like annoyance. "Okay, okay, for riding, right? I guessed that much. What I meant was, do you race them or breed them or what?" See, I knew about things—my tabula wasn't completely rasa. I just had to relax, and surely I would remember the rest.

I shuddered. Assuming I really wanted to.

He shook his head, more to himself than in response to my question, and sighed, and went back to his silent riding.

None of my business, I guessed. I tried being quiet again, since that seemed to be how the man liked it and he was in charge for now. But the insect-buzzing, hoof-beaten stillness bored into my head and echoed there. I had too much catching up to do, damn it. And the nightmarish bits of my past that edged in at my memory…?

That, I couldn't deal with just yet.

"I didn't mean to pry," I said finally. Even an apology was better than no distraction at all. "It's just that... I don't seem to know anything, especially not about me. Knowing about you, or your horses... anything would be better than knowing nothing." I studied my horse's mane and felt sorry for myself. "That's all."

Clop, clop, clop.

"Cow horses," he said abruptly. "Lost part of the remuda in Injun Territory."

I didn't want to press my luck, but... "What's a remuda?"

Clop, clop, clop.

"Horses," he clarified.

Ah. Cow-horses. For the herd. Where we were heading, a day's ride thataway, closer than any doctors. Pieces were fitting into place—so why did this seem so foreign to me?

I suspected that if I asked more questions, the cowboy would force himself to answer them. More or less. I also suspected it would continue to feel like pulling molars. And I couldn't think of any more questions besides personal ones, which might prove especially unwelcome. So I just settled into the rocking of the horse, and I felt hotter and hotter in the Kansas sun.

My wrists and ankles ached. So did the muscle where my neck slanted into my left shoulder. When I wondered why, fear all but gagged me, so I tried not to wonder. After awhile I felt too sore and tired and miserable to talk anyway. At one point Garrison glanced back at me, frowned, and reached over to put his hat on me again.

Over the bandana, it didn't fall onto my nose.

I must have looked confused, because he actually offered an explanation. "Sunburnt," he said, before turning away.

Foolishly, I felt like crying—not because of the hat, but from the strain of guarding against the terror inside me. I longed to hurry, like an almost physical need to escape, but no longer knew from what, or where to. I wanted to strike out, to fight, to scream—but why? At him? I wanted what I couldn't even visualize: my own clothes, my own place, my own things. My name. Something awful had happened, and everything was gone, and how could that feel like relief?

Now I stayed quiet, head down and hat blocking my sight of almost everything, so that the cowboy wouldn't look back and notice tears dripping off the tip of my nose or sliding, salty, into my mouth. I wanted to know who I was. I wanted to wonder about that without it hurting.

We rode on, and eventually I began to drift. Not just my thoughts. My body. As if on the cellular level, I began to simply… evaporate. Like, into nothingness.

Summer heat melted into cold, canned air.

The chirr of grasshoppers and birdsong faded beneath white noise, electric beeps, indistinct conversation and music and movement.

The shadow of the hat vanished, allowing a laboratory's sterile fluorescence to wash across me—along with menace.

A man's familiar voice demands, "Do you see that? Is it her? Hey, what are you—"

For a horrible infinity, I can

't move, can't breathe, can't scream. I don't exist.

Then I solidified. My hatted head came up and I screamed my fool tonsils out.

Or I started to.

Apparently, horses don't appreciate screaming. Mine didn't, anyway. In three bunched hops, it launched me out of the saddle, which shut me up even before I hit prairie. I tried to roll to my feet, in case I needed to dodge flailing hooves, but I hadn't angered the horse that much—it chose flight over attack. It could only escape as far as Garrison's rope, though, and in the meantime, I couldn't inhale. At all.

This time, I knew why. Me. Ground. Impact. That didn't stop the panic that burst into my head, the longer I went without oxygen—or the sheer relief of suddenly, being okay again, sucking in a couple of lungs full of hot, Kansas afternoon. Yes. Here. Safe.

Despite the horse-diving, something about this place felt infinitely safer than wherever I'd begun to drift, even if that place hadn't been real.

And it hadn't. I'd fallen asleep. I must have, right? The light seemed funny—low and reddish—and we'd ridden down lower than the rest of the prairie, by a creek that I didn't recall approaching. Clusters of honest-to-God trees grew here, sheltering the water and the greener grass that the wet-footed remuda was already taste-testing.

Garrison somehow made my horse stop hopping, then swung his own around to stare down, down, down at me. "You hurt?"

I blinked blearily at the twilight around me, increasingly confused by my panic and by filmy remnants of that nonsensical… dream. Let's just call it a dream. Then I registered the question. "I don't think so?"

He slid off his horse—on its left side—and extended a helpful, leather-gloved hand. When I took it, he yanked me easily to my feet.

"Nope. Not hurt." Then I collapsed downward.

The cowboy caught me deftly, hands solid on my waist, and held me until I'd managed to test my marginal ankle and prop my jelly legs beneath me. How was he not exhausted, after the ride we'd had? Wasn't it harder to ride bareback?

Maybe so, but he seemed about as weak as an oak tree... and about as chummy, too. While I felt tempted to go on leaning into him—just tempted, mind you, drawn to the meager familiarity of this man—he stepped quickly back, leaving the technicalities of balance to me.

"I think I fell asleep," I confessed, my tongue thick and my voice hoarse with dryness. Without looking at me he nodded an affirmation. "How'd I stay on the horse?"

"Throwed." He started switching the saddle off of my horse, and the bridle off of his, onto a third horse altogether.

"Only after I screamed. Before that…."

"Smooth gait." But he didn't ask about the screaming.

I merely swayed and watched. In very little time Garrison had not only rubbed down the two original horses with handfuls of grass, but was mounted yet again, whooshing the rifle out of its scabbard and laying it across his lap.

"Best collect wood fer a cook-fire," he instructed, and I realized he was going somewhere.

"Can I have some water?" I asked, focusing on the canteen hanging from his saddle. He'd left a rolled blanket and the saddlebags sitting on the ground, but had kept the canteen. My mouth felt incredibly dry.

He stared at me for a long moment, like I'd said something really dumb. Then he untied the canteen strap and handed it down to me. "Best refill it, when you're done," he drawled, then rode up and out of our little campsite as easily as if he was glued to the saddle. I didn't think about his instruction at first and merely gulped more tinny, hot water. Only once I'd satisfied my thirst and taken a few deep, head-clearing breaths did I realize that he meant for me to refill the canteen in the creek.

Where the water was cooler and not at all tinny. No wonder he'd stared.

Whoever I was—had been—this level of stupidity seemed a new and unpleasant sensation. How did I get so dumb? Other than the amnesia part, that is? I stared at the remaining six horses, who were loosely tied together and happily dining on too-tall grass, and I felt so lost, so displaced, that I almost started crying again. Why was I so sure I'd never been this close to such large animals before? Why had I thought we would refill the canteen from some other, easier source than the creek?

Even as exhausted tears began to well, I found and grasped some shreds of dignity. I felt dizzy, scared, hurt, unsure of everything—including myself. No wonder I wanted to sob!

But it wouldn't help.

When I limped over to the creek and let the cool water run over my feet and ankles before refilling the canteen, I started to feel marginally better.

Best collect wood for a cook-fire, he'd said. Cook-fire meant something to cook, right? Food. Dinner.

My stomach growled. I draped the canteen strap over my shoulder so that it crossed my chest—somehow that seemed safer—and valiantly limped off in search of firewood. I had to watch my step, and still gouged my bare feet on burrs and rocks, but I'd collected a decent pile of wood from up and down our little creek before I heard the gunshot.

The horses' heads came up, ears perked, at the same time mine did, but they didn't look as stunned as I felt. That was a gunshot, wasn't it? Cowboy Garrison had taken several guns with him. It was probably him.

Right?

I tried not to worry as I collected the pile of wood in front of me, between the now-alert horses and the creek. Then I attempted to figure out how to start a fire with nothing in my borrowed pockets. Rub two sticks together, right? But knowing and doing were two different things—stick-rubbing did not come naturally to my hands, anymore than kneeling on rocks did to my poor, bare knees, and I soon gave up. Besides, I was worried.

Suppose, just suppose, the shot had come from someone else's gun? A bad guy's gun? I hadn't heard any return fire, which would mean the bullet had found its mark. Suppose I was alone now, in the middle of an empty Kansas, with six horses I couldn't ride and a bunch of wood I couldn't make into a fire and nothing to cook anyway? Not to mention a murderer on the loose, and me wearing no more than an oversized, overlong man's jacket, knowing nothing except that something bad had happened?

Before I could reach full panic, several of the horses lifted their heads and nickered. A returning whinny sounded from over the knoll. What if it wasn't—but it was my close-mouthed companion, rifle holstered and a dead bird hanging upside-down from the saddle. He pulled the horse to a stop near me, swung easily down, and took the dead bird off the saddle.

I noticed that the dead bird had no head.

He stared at my collection of wood in what, if he'd been the least bit expressive, might have been disappointment. "Pluck the turkey," he said, and before I knew it I had a horrible headless dead bird in my hands.

He began to unsaddle Horse Number Three, and I stared at the fine-feathered corpse in rising dismay. My instincts screamed to drop it—but its ex-head was a raw, bloody wound, and I didn't want to get it dirty. Not that it needed to worry about being sanitary at this point.

"I am absolutely positive I have never done this in my life," I announced, hoping my voice didn't shake, while Garrison eased the saddle to the ground.

He paused to stare at me, still deadpan, but now a real incredulity shadowed his eyes. "Never plucked a bird," he repeated. Then he stepped closer, took my poultry-free hand, and turned it palm-up for inspection.

He shook his head and dropped the hand and returned to his horse-tending. He removed the saddle blanket, grabbed a handful of dry grass, and began to rub it over the horse he'd just ridden, where its back had gotten sweaty. I stared after him, torn between insult and uncertainty.

He must have realized I actually needed instructions, because he drawled, "Pull the feathers off."

The dead turkey—which, by the way, seemed far skinnier than I imagined a turkey should be—made me increasingly uncomfortable. "Ah," I said channeling some of that discomfort into sarcasm. "Of course. I pluck the turkey by pulling its feathers off. How simple. Thank you for that detailed tutorial."

He was staring again, over his shoulder. Fa

scinated? Disgusted? I had no way to tell, but the force of his direct gaze disquieted me even more than holding a murdered bird—I would hate to have this man angry at me. In any case, he left the horse again to pace over to me and take the bird. My relief was short-lived when he held its scrawny corpse in front of me by its feet, grabbed a fist full of feathers, ripped them right out—complete with an awful, tearing noise—and handed it back to me.

He opened his other hand, and most of the feathers fluttered away.

"Pull the feathers off," he repeated, and turned away with a final warning. "Right harder to pluck, once it cools."

I sooo didn't want to pluck that bird. The words you can't make me swelled into my throat, but I swallowed them back. This felt so wrong. Eating shouldn't be this complicated.

And yet, if I didn't pluck, I might not eat. I could see that in the set of the cowboy's shoulders.

And he was still busy with the big, sulky horses.

At least I was starting to visualize where I wanted to be, instead of here. I wanted civilization. I wanted a place with not only doctors, but… but restaurants. And stores.

See how much I began to remember?

But in the meantime, I plucked the damned turkey.

You know how a lot of things aren't as bad as you fear they'll be? This one proved worse. I kept thinking I saw little bugs in the feathers, and cringed from them as much as from the ripping sound. I felt sorry for the slowly balding headless dead bird. It didn't help my mood that, once he'd finished checking the horses, Garrison squatted beside my pile of wood, threw a third of it aside like trash, easily formed a tent with some more, and lit it with a match from his saddlebag.

Of course. Matches. Make it look easy.

Rip. Downy feather bits floated up my nose and made me sneeze. Rip.

In the end it was Garrison who cooked the turkey, too—Garrison who knew how to gut it, Garrison who knew how to prop it over the low-flame fire on a stick. My job was simply to turn the stick, like some organ-grinder's monkey, so that it would cook evenly. Sad to say, I doubt I did even that very well. I kept getting distracted, watching the way this man incessantly worked.

OverTime 1 - Searching (Time Travel)

OverTime 1 - Searching (Time Travel)